I live in a small town in rural Madison County, North Carolina. My husband was born and raised two counties to our north before his homesteading parents traded their back-to-the-land hillside for nearby Asheville’s job market and indoor plumbing. North Carolina born and raised, my husband feels at home here in Mars Hill. While I love where we have landed, home is harder for me to come by. I was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, but in some of the stories I tell about myself, the world revolves around a country church in Jamestown, Arkansas, near the cattle farm my grandparents bought after World War II. Even though I spent my early childhood in suburban New Jersey, I often lead with the years my family spent chasing my father’s operatic dreams in a newly reunified Germany. Atlanta, Georgia, is another place I could claim. Most of my father’s family has lived across the metro region for generations. From towns and suburbs that used to be mapped along predictable perimeters—white and black, red and blue, in and out—older folks in my family talk a lot about the way things used to be. Precious memories? They do more than linger.

My great-grandfather on my mother’s side could throw his voice, a party trick he loved to play on friends and strangers alike. Out of sight, he projected his voice to sound close to those who could hear but not see him, often to hilarious result. I throw my voice, too, but it’s different. Raised up in all kinds of places among all kinds of people, I can pitch myself to be heard in all kinds of registers. But throwing your voice for fun is different than calibrating or code-switching or contorting yourself in the name of legibility or even love. Something happens when we cast ourselves out. This body, then, is eager for its own homecoming. And what kind of home will I make from porches and farms and city streets and altars and alto benches alike? What kind of home will claim me back?

Raised among people raised to stand and sow and surrender and sing, the drawl I keep in my back pocket has standing competition from another way of being and believing that runs bone deep. What to make of my formative years in a former country? Ostalgie is my ground truth, even if the country I long for was already disappearing by the time I arrived. Feet planted in soils both native and foreign, I look for myself—and others, too—in and among the dissolved and disappeared and discontinued and disrupted everywhere. Hell-bent on home, I journey, one heartbeat at a time. What can I make (out) from here? What about from there? Who needs to be seen? And what remains to be said?

My particular birthrights demand allegiance to more than one creed or constitution can hold. My people are farmers and homemakers and salespeople and teachers and country doctors and politicians and church musicians and organists and mothers and fathers and sisters and brothers, too. My people have roots that wander before circling back. My inheritance is a garden and its tilling, a table and its setting, a play on opening and closing night, and a whole body attuned to the vagaries and victories of hearts and minds broken and still breaking. Mine, then, is holy wonder that has not forgotten where it comes from. How do we revel in possibility while honoring the deep pain that courses beneath the surface of so many nations and states and nation states and states of mind? If I could, I would grow a country that looks beyond its borders to neighbors everywhere. If I would, mine could be a people that refuses distinctions between winners and losers, firsts and lasts, between wellness, wholeness, and too many wells of difference pathologized at the cost of our very humanity. Mine is a country yet to be. I wonder about yours. Will I ever know theirs?

When I honor the differences that divide so many things—and people and places, too—I remember that history is a powerful current that carries too many of us away from one another. But Her stories might carry us all the way home. Yours might, too. Traveling across roads my forefathers and mothers understood as wholly theirs, I remember others who came before. They, too, are still speaking. Mine then is a pilgrimage less interested in salvation than in sweet surrender. This is no salvage mission to reclaim those deemed fittest, but a deep reckoning with keys and kingdoms alike. It is something to notice when your own feet falter, but choosing to walk a mile in someone else’s shoes takes a different kind of discipline. When will I ever learn? And you? What about them?

A few months ago, some took to the nation’s capital. For many, this storming was a manifest destiny moment generations in the making, a rousing patriotic love song to a nation perceived as both lost and losing. The images of the insurrection are sobering, but they are not surprising. The fragility of the assumptions so many of us make—about ourselves and others—is always on display somewhere. The great democratic experiment for which this nation is known around the world has long proven to be aspirational for many closer to home; especially those not yet included in the “we” presumptuously named in our founding documents. Whose America? Yours? Mine? Some kind of ours? What about theirs?

The premise that something needs to be great in order for it to be of value is one of this country’s most pernicious falsehoods. Greatness distracts from the greater good. It also keeps us counting the score, as opposed to measuring the cost. If this country wants to be for, of, and by “the people,” then there is work to do to remember one another along the way. A dear friend and sister colleague, Dr. Georgette “Jojo” Ledgister shares a beautiful teaching about the ground we stand on. Congolese born, Jojo speaks truth to power in several languages. She recently reminded me that humility and humiliation share common ground in their francophone etymology. Humus, then, can grow all kinds of things. What am I seeding? What about you? What about them? It is my truth that so many are so frightened of being humiliated that entire worlds are lodged in our throats. But if we exchange hate and heritage alike for the kind of humility that listens and loves its way toward liberation—yours, mine, ours, theirs— what kind of humanity might flourish?

Images of a capitol stormed can be leveraged to confirm or deny the tales tall and sometimes even true that this country has been telling on itself for centuries. I am a scholar of American religions who thinks deeply about the stories we inherit. I love to tell the story? Not so fast. My work unfolds in the in-between spaces where texts and readers go the distance between intention and impact. Not just one reading, then, but the many misreadings, too. If we consider the stories we are also always being and becoming, there are questions to raise about how we read one another. What kind of heuristic can hold this moment’s truths and untruths? And those of the many moments before and after? Or put differently: What happens when my gospel truth is a story you would rather deny and dismiss? What happens if your story is gospel truth, too? And what about those for whom the gospel only applies to a particular book or tradition or religion or people? As a nation, this country has long subsisted on a diet of fiery brimstone that preaches promises of conditional grace to a limited elect. But what if we turned our gaze from eternity to the everyday? It’s not greatness that the soul of this—or any—nation needs. It’s goodness. When we are consumed by our own righteousness, salvation-as-strategy doesn’t seem to see or mind the dark shadows it casts. But what if no one is coming to save me, or you, or even us? What if we are all there is? What kind of gospel makes room for them, too?

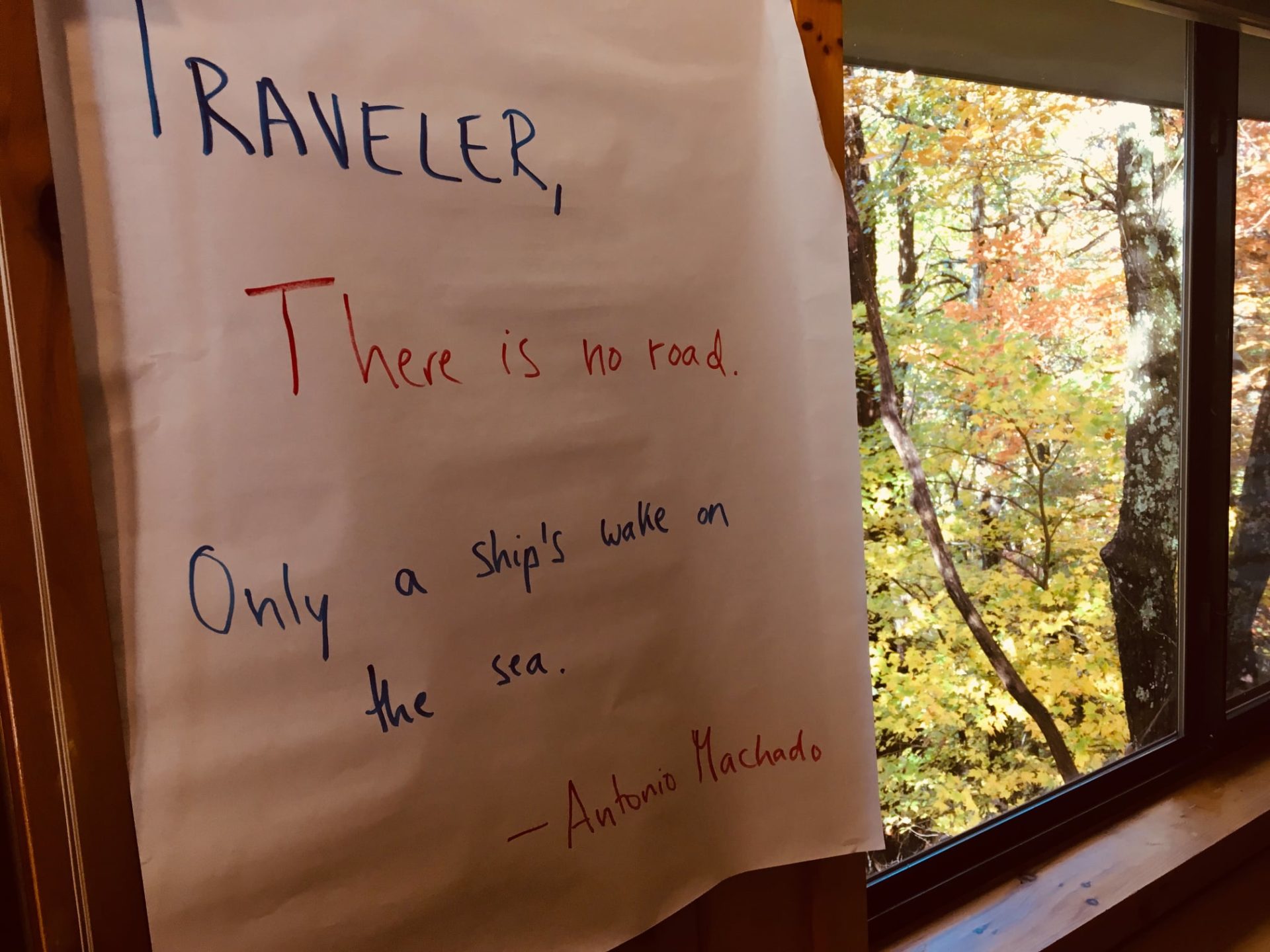

Sometimes, I remember all the way back to the founding image of that famed and faulty and ultimately fictitious city on a hill from which this nation has charted a course that many understand as divinely inspired. For centuries, first colonists and later citizens of this country have been arming themselves in a rhetoric that preaches mine not yours, that prizes independence above all else. Were we to learn from this season of compounding assault, what kinds of questions would we ask about other stories that warrant reflection and reckoning before their long overdue retirement? What am I willing to forgo for a different kind of freedom? What about you? What about them? I love a good metaphor, and alliteration is one of my favorite devices. What, then, to write in order to right or return or refuse or recast this ship that has long been sinking from sea to shining sea? There might not be enough metaphors to fix what is ailing us, but the poets have long known that centers do not hold. With the bedrock of this country claimed for someone else and something more, I wonder about the relationship between you and me. And what about them? What will it take to unleash unlearning itself on so many different scales at once?

These reflections come from places, including a home I am trying to make in a rural county with dueling reputations that have a lot to teach about this country’s inborn dichotomies. Nicknamed “Bloody Madison” and the “Jewel of the Blue Ridge,” some of this county’s origin stories tell on one another. Madison County first earned its reputation in a legendary Civil War showdown that pitted neighbor against neighbor before leaving thirteen Union sympathizers dead. Almost 100 years later, a young Vista worker was brutally assaulted and murdered in a case that remains unsolved. Descendants of the slain and culpable are alive and well in this county where the perimeter of belonging is measured by the number of generations that count some in and others out. But the “Jewel of the Blue Ridge” is here, too. A rebranding rooted in mountaintop vistas, this metric forgoes a deep dive in favor of the casual drive-by. If we stick to the highways—of this, or any place—we might notice only the brave and the beautiful. But if home is where the heart is, what about the rest of the body? The underbelly is teaching, too. Will I have ears to hear? Will you? We will? Will they?

I spent a long chapter of my life studying Appalachian culture and music. The place of Appalachia is often ascribed a kind of storied poverty that competes with this country’s image of itself as a bastion of progress. A thinly veiled excuse to spend a few years in the mountains singing the hymns my mother was raised on, my masters degree in Appalachian Studies trained me up in the ways of anthropological inquiry and the impossibilities of participant observation. I spent two years researching the singing traditions of two small missionary Baptist churches. What I learned above all else is that phenomenological bracketing and methodological maneuvering are no match for Spirit moving. From my position on the alto bench, it didn’t matter what my research questions were once the choir started singing—and there are always more questions to ask about all that remains to be named and claimed in a country unaccustomed to holding itself accountable. I might have started out on the hunt for a kind of music that would remind me of home, but the takeaway was all about being and belonging. In the presence of others, I remembered my own. And then I went back for them.

Growing up, my mother liked to remind me and my siblings of our roots. Before leaving the house she would often say, “Remember whose you are.” I’m sure my mother would prefer that I remember this invitation first and foremost in relation to the Jesus she loves. And while I remain open to all kinds of spiritual shenanigans, I prefer to hear in this phrase an exhortation to remember my brothers and sisters, and neighbors and strangers, too. Whose am I? Whose are you? And whose might they be? When we abdicate responsibility for one another to powers higher and unseen, we run the risk of deferring not only flourishing in the here and now, but life itself. This world is not my home? There is no eschaton worth dying for, no matter what the old hymns say. As for deferral? It comes at the cost of my humanity. Yours, too. And also always, theirs.

My mother is not alone in building her hope on things eternal. Many make sense of this world by claiming it as a prelude to what must surely follow. When I start digging into the systems and stories that live deep within, I am always mindful of those who understand this particular place as a stepping stone to some kind of greater glory. Even so, I wonder what it will take to reclaim a different kind of ownership over the here and now. The full armor of God, then, can be too much to bear when we leverage the sacred to authorize ourselves above all others.

I once wrote a dissertation about the particular ways we talk about religion in this country. Titled, “I Love to Tell the Story: The Competing Exceptionalism of Appalachian Religion,” it was a treatise on all we must reckon with in the attempt to parse and make peace with the many pasts we inherit. Birthright, then, is not just privilege, but due process. How much can and will we do with what we are afforded? And what stories will we divest from as we trade righteousness for relationship? When I look closely at the foundations of this country, I see the pillars of exceptionalism and extremism joined by the rallying cry of evangelicalism. Will there be any stars in my crown? It is one thing to look at insurrectionists with horror. But to look deep within for evidence of ideology that lives in me, too? For to know yourself or any other as exceptional is the fulfillment of all kinds of prophecies. What is it about all-consuming patriotism that keeps our gaze averted from the leveling field of personhood? What does it mean when we hope to save no one but ourselves?

This season of endless assault is not the only act in town. Generations of organizers are standing on the shoulders of giants. The ancestors, too, are showing up. They’ve been here all along, their bodies and spirits challenging and changing the very premise of how power works and on whose behalf. Amid unrest and reckoning, then, is the work of many hands. What am I holding onto? What about you? What about them? Calls for unity presuppose a kind of shared purpose around which you and I might rally. They might, too. But I don’t see a prefabricated home for such an enterprise. What kind of foundation can you build with folks running for the hills? What about the people who live there, too?

Yet another chapter of my life took place in a former East German state where statues and systems toppled daily. If I relied on memory alone, I would lift up a story of reckoning completed. But history loves to repeat itself and it doesn’t matter how many Russian soldiers decamped to the motherland. Today, Germany, too, struggles to maintain purchase on things like truth and justice. I recently reconnected with a friend I met in the small town of Neustrelitz in the early 1990s. Navigating all kinds of growing pains, we frequently spent time in her family’s home on the outskirts of town. Together, we stood on a huge wooden swing and sang songs about freedom. Where have all the flowers gone? Not just this week, or this capitol, then, but in each and every time and place. It is true that a new administration is now taking its turn. Some changes are in the works with others surely to follow. But what of the many across this nation state, and so many others, who are still looking for a different kind of win?

If Insurgency Wednesday happened—and it did—then what kind of resurrection can we hope and work toward? This “we” of which I write is more fragile than all kinds of democratic ideals. Desecration takes on many forms, and while it is good and right to note treason as one line in the sand, I wonder how many more we cross—unawares, unwittingly, and with eyes wide open—in our attempts to hold onto our own slice of the pie? The move from me to we travels on roads made by going the long way ’round. I wonder then, about what might truly be exceptional about this moment? It’s not the violence or insurrection or even the sedition. It is also not the habit of leaning first—and sometimes only—on the wisdom of our own understanding.

I know what the allusion of arrival feels like. I know it from the unfashionable midcentury ranch my husband and I purchased almost two years ago. This structure—hard won and hoped for—falls within the category of “starter home” in a nation that just keeps outsizing itself. But for us, it’s perfect. I also know something of achievement from a degree and title that give way to ladder upon ladder. Mine, then, is a threshold gospel that preaches always already worthy and enough is enough is enough. In the gardening of this hilly half-acre plot, we are digging deep and tending things that grow right here at home. So many things will die here, too.

Even as signs of spring give way to summer, I wonder about that which we glean from last gasps of bodies and beliefs, of citizens and countries alike. What I know about death, I learned from my grandmother’s decline. A humble housewife and beloved matriarch who went back for her high school degree to graduate alongside her children, I never heard her utter a mean-spirited word about her extended family and community. Hers was an inheritance we readily remember as being too poor to be complicit in all this greatness. In, then, but not of. But here’s the thing: in her mental decline, the past resurrected itself and spoke into a dying future. No longer aware of herself, my grandmother reverted to language learned in her childhood where the unequally yoked burdens of so many systems and stories took root lifetimes ago. My mother was shocked when racial slurs came out of a mouth that loved to sing about sweet hours of prayer. But to be shocked at evidence of this country’s social contracts as they played out in my beloved grandmother’s diminishing mind is to shy away from the very same contradictions and confirmations that persist today. Remember whose you are? What about me? What about us? What about them? Can we love one another enough to search for the whole truth? Even when it’s ugly?

I still don’t know where home is even though I am getting to know my neighbors, which is often a first step along the way. We wave at one another as I walk miles each day across our rural county. There are all kinds of people right here, in this place both beautiful and broken. I wonder what it will mean—and take—to fit in. I wonder whose names I will bless on my deathbed. Should my mind go, what curses will betray me? What will I keep learning from here? If map is not territory, then nations are not homelands. What, then, will a life lived in this place ask of me? I wonder what your home place asks of you? What about ours? What about theirs?